A community is building up through invisible cooperation

He senses invisible collaborations that then turn into action and community. He speaks to people at the local market to find out how the local community could be strengthened. He works outside institutions because there he has more room for manoeuvre. The goal is always the same: to make living in Törökszentmiklós better. Interview with László Hajnal, first grantee of the Roots and Wings Foundation’s Small Town programme.

After graduating from university, you lived in Budapest and then moved back home to Törökszentmiklós. Did your decision have to do with you wanting to change things in your hometown?

I left Törökszentmiklós very soon, at a very young age, because I was missing the cultural diversity the big city had to give. After a while, however, you just cannot go to every concert and see every theatrical performance – then more personal relationships become increasingly important. This is how I overcame with local patriotism and became a Törökszentmiklós resident again. What matters to me is what I do – it’s not an external mission whereby I work for others with dedication.

Do you know anyone else – say from your own generation – who came back to Törökszentmiklós after graduating from university?

This is also interesting because I can’t work with my own generation in the first place. Rather with older or younger people. Not many friendships tied me here when I was in elementary school.

Can you point to some kind of a turning point when you started thinking about coming back?

At the Újpalota Community Centre, where I got socialized in my profession, I started working in a tower block housing estate environment and noticed that everyone was rootless. People got into the big city, or from downtown to the suburbs in hopes of a better place to live – then they became lonely. Everyone was looking for their roots, but when I talked to elderly women, it turned out that many hadn’t been in their home village for 40-50 years.

Another important thing was the freedom I had a chance to experience when I started working in the community centre. My boss was Árpád Kelemen, a community development professional; he said, why don’t I have a look at the place and talk to him in a few weeks about what I wanted to do. So I started to snoop around and look around, I talked to people and helped with the existing programmes. Then, I came up with my plans. One of the outcomes was a gallery that I founded for career-starting artists. It still operates today.

We went out to the housing estate, and under the guidance of community development master professional Feri Péterfi, we started building a circle of friends called Nyírpalota Társaság. Slowly, I came to realise that people have to join their forces and then the world will be a much better place to live.

Then came the turning point in my personal life that was appropriate for me to quit my work built up in Budapest and move back home. I realised that focusing on genealogy and city history here at home is definitely a much greater experience for me. Here, I can do more for myself, for my own environment, than in a big city.

How do you work in Törökszentmiklós as a community development professional? How do you find issues and causes?

What I’ve noticed is that in the countryside the development of the community is not driven by formal things, but rather by invisible threads, invisible collaborations based on the fact that we live here in this town, for which we should do something together, because there’s so much more that binds us together than what separates us.

| LÁSZLÓ HAJNAL cultural organizer, community development professional (Törökszentmiklós, 1964) He spent his childhood at a farm school in the Great Plain, where his teacher parents gathered the farming community together as a “lantern”. He graduated from the University of Pécs with a degree in cultural organisation and studied community development at the Civil College in Kunbábony. He started his professional work at a tower block housing estate environment at the Újpalota Community Centre, and then went on to work for non-governmental organisations, small town community cultural centres and local communities. Stations in László’s professional career: Zsókavár Gallery (Bp.) Summer University of Early Music (Tokaj) Association for Óballa, Village Day Lukács Mozgó Youth Cultural Center Törökszentmiklós Values Club Street Music Festival (Törökszentmiklós) He worked as head of the Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County Office of the National Institute for Culture until 2017, and then as a local mentor for the national cultural development programme “Acting Communities – Playing an Active Role in the Community” run by the Museum Education and Methodology Centre of the Open-Air Ethnographic Museum. At present, he works as a socio-cultural animator for the Local Council of Kőtelek. He is holder of the Pál Beke Memorial title (2018), for his value-creating work in the field of community culture. |

How do you notice invisible threads?

I go to the marketplace and talk to people.

When you go to the market, is there a topic in your head that you want to talk about?

No. The topic is given by the people.

How should I imagine that? You go to the market and talk to the people you know?

We say hello to each other, exchange a few words, and with some of them we stop for a longer time and are glad to see each other. From these conversations, it becomes clear to me in what direction I can contribute something – as a socio-cultural animator – to strengthen the community here.

How do small conversations turn into action and a community?

I always approach community development from the direction of socio-cultural animation. Obviously, here too, the local community wants to accomplish a lot; I believe that a person working in socio-cultural animation has to “take away” the obstacles in the way of intentions, one by one. You have to look a little ahead, and I have that ability. I try to find topics that also affect people emotionally, and then a hundred, five hundred, two thousand – it depends – people will turn up at my events.

In Törökszentmiklós, it is very difficult to take a path in socio-cultural animation so that not only professional ideas are realised, but they are also in sync with the needs of the local community.

Why don’t you work as an employee of a state or municipal institution?

I’ve tried to get into the community cultural institution here two or three times, I once worked there for a short time from grant money, but they fired me because this kind of mentality, this kind of thinking just did not fit into the official framework.

Which part of it was problematic?

I received the feedback – and this has accompanied me for many years – that I am self-willed. A few years ago, it became clear to me that it might be better this way, outside of an institution, if I wanted to work free from the limitations imposed by the maintainer or by local dependency systems; these can hinder the professional work itself.

How much room for manoeuvre do you have now?

A lot, I think. Whatever I come up with, I can do it. By the way, I work in socio-cultural animation so I have practical experience. Only, it always comes from somewhere else – from the county level or from the surrounding local communities.

What gives you room for manoeuvre outside of structures? Where do you get your money from? How can you enforce your approach in this setting?

Since I’ve been home, at least three mayors have been in office. With each of them, I found – even though they belonged to different parties – that although they did not intervene for me to get a job here, they did support me. I always get some small seed money from the local council to carry out my ideas, and then I knock on the door of local businesses, or some grant money pours in.

The municipality has a lot of expectations for the community cultural institution it operates, and the institution tries to come up to those expectations with very little money. Civil society can no longer enter this closed world. That said, in Törökszentmiklós my professional freedom as an NGO person is greater than in my own jobs so far. There, for example, they prescribe very strictly whom should be invited – the maintainer has specific demands and professional considerations are relegated to the background.

How do people find your events? Do they go because of your personal credibility, or because of a topic that others have failed to find?

Because of the topic. There is, for example, the Törökszentmiklós Values Club, which is now in its sixth year, and so far we have given 35 lectures. Those six years indicate to me that well-chosen topics attract interested people. By the way, the club is driven by local patriotism, the emphasis being on why we can say about ourselves that we are from Törökszentmklós. I try to put my tentacles into the most unexpected issues and find out what to focus on next month.

Can you give examples?

Of course. Let me give you a negative one and a positive one. I thought that the topic of economic self-sufficiency would be a huge hit, because now our agricultural town also entirely depends on supply systems. However, there are other possibilities. I invited, among others, two mayors who have already embarked on the path of economic self-sufficiency. I rented out the great hall of the community cultural centre, but hardly any interested people turned up. This topic is “far away”, it’s not yet timely here.

When we talked about the farm world around Törökszentmiklós, I thought it affected only one particular social group, but in the end the small hall of the centre proved to be insufficient for the over hundred interested people who turned up. Everyone had some kind of nostalgia, some personal involvement. Or in the same way: I invited the former director, who had put the padlock on the institution, to present a job that was flourishing in the 60s and 70s but no longer exists today – that time, the hall proved to be to small again.

Can you give more examples of how you realised what was interesting to people and how it all turned into a community?

The whole story of Óballa is like that. I bought a house in Óballa, which is ten kilometres from here, but is part of the city administratively; a very bad road goes there. I found old pictures in the house, I asked the neighbours who was on them, then a photo collection process started, we digitized the photos and organized an exhibition in the yard of the closed school. This eventually turned into the first village day in Óballa, because people said that once we get together, we should eat something, and then they said we needed some music. Then the annual church fair – which was scheduled for the next day and is traditionally an important holiday there – was brought forward by the parish priest of the time, so that at least many people would turn up. By today, the Village Day has such an impact that former villagers still come back to attend it today. It’s not a real village day, by the way, you don’t have the traditional line-up from the mayor’s opening to the star guest. It’s actually a mini- festival taking place at three venues, but I prefer to call it Village Day because then more people will come. We have just organised the sixteenth – usually we have 1500-2000 participants.

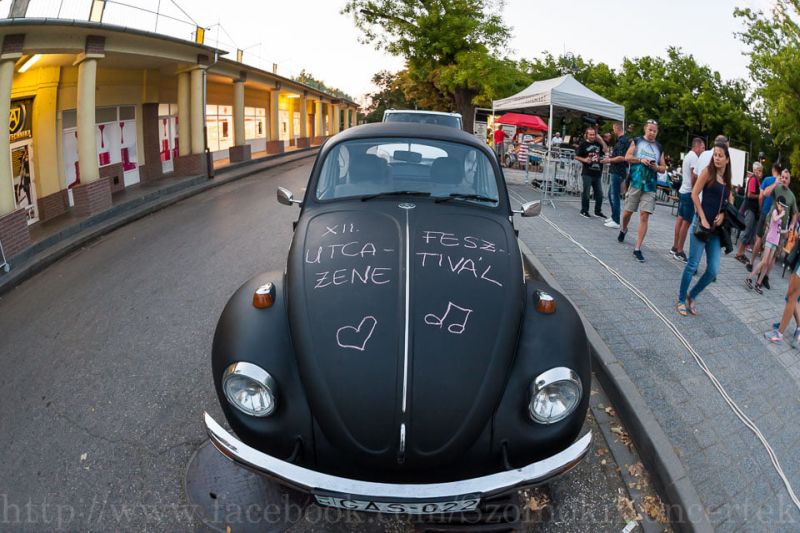

The street music festival, which started from Lukács Mozgó (the town’s old cinema – ed.) is something similar. There always used to be concerts happening in the foreground, but there weren’t many of us because people couldn’t see through the door that there was an event going on there. So we unloaded the platforms onto the sidewalk and brought out the speakers so that the concert would happen there. This went on as long as I could rent the Lukács Mozgó. After the involuntary end, I didn’t want to let go of the process: just now, in September, we held the 12 th Street Music Festival on Kossuth Square: the event started with classical music, and then there was jazz, blues and classic rock, with dancers and stilt dancers during transition times.

We dash through Kossuth Square every day, without really being aware of its original (300-year-old) community function that it was created to serve. Routine small-town public space using habits are changed for an evening with the help of live music, which is another opportunity for personal encounters, conversations, and listening to the diverse musical styles “smuggled in”. Above all, I want to strengthen the local community with the help of live music by making use of the obvious meeting point on the main square. For a night, the casual restaurant and direct – stageless – live music transforms the town’s central – and arguably most beautiful – square into a musical community space!

Where will you get with the support of the Roots and Wings Foundation?

I’m not starting a new activity, I want to continue with the running programmes in a more profound and effective way. I don’t want them to be my self-realization, but to attract more and more NGOs who see them as opportunities for participation and for introducing themselves.

It would be good to create a socio-cultural round table in the city, where the representatives of the local council, the public cultural institution and the representatives of civil society could work together with greater openness and greater tolerance towards each other’s things. We need to realise that we have a common goal: to make life here better.

(Iván Bardócz)